Translations of Brazilian IP Rules

Ordinance INPI DIRPA nº 16 – Guidelines for the Examination of Patent Applications – Content of the Patent Application.

Full pdf version of the English translation available here.

ORDINANCE /INPI /DIRPA No. 16, OF 2 SEPTEMBER 2024

Republish the Guidelines for the Examination of Patent Applications – Content of the Patent Application.

THE DIRECTOR OF PATENTS, COMPUTER PROGRAMMES AND INTEGRATED CIRCUIT TOPOGRAPHIES, in the exercise of the powers conferred upon him by Decree No. 11,207, of 26 September 2022, and Art. 93, item V, of the Internal Regulations of the National Institute of Industrial Property, ADMINISTRATIVE RULE/INPI/PR No. 09 of 6 March 2024, and CONSIDERING the contents of file No. 52402.011283/2023-91,

RESOLVES:

Art. 1 Republish the guidelines for examining patent applications – Patent Application Content (Block I).

Art. 2 Resolution No. 124/2013 is hereby revoked.

Art. 3 This Ordinance revokes ORDINANCE /INPI / No. 15, OF 29 AUGUST 2024, which republishes the Guidelines for the Examination of Patent Applications – Content of the Patent Application.

Art. 4 This Ordinance shall enter into force thirty (30) days after the publication date in the Electronic Industrial Property Journal.

ALEXANDRE DANTAS RODRIGUES

Director of Patents, Computer Programs and Integrated Circuit Topographies

ANNEX I

Guidelines for examining patent applications – Patent Application Content (Block I)

Reference: Case No. 52402.011283/2023-91 SEI No. 1073725

MINISTRY OF DEVELOPMENT, INDUSTRY, COMMERCE, AND SERVICES

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF INDUSTRIAL PROPERTY

GUIDELINES FOR THE EXAMINATION OF PATENT APPLICATIONS

Contents of the Patent Application Title, Specification, set of claims, Drawings and Abstract

Block I

SUMMARY

CONTENTS OF THE PATENT APPLICATION

Paragraphs

| Chapter I | |

| TITLE | 1.01 |

| Chapter II | |

| Specification | 2.01 |

| Presentation | 2.01 |

| State of the Art | 2.03 |

| Technical Problem to Be Solved by the Invention and Proof of the Technical Effect Achieved | 2.06 – 2.11 |

| Industrial Applicability | 2 |

| Descriptive Sufficiency | 2.13 |

| Deposit of Biological Material | 2.17 |

| Sequence Listing | 2 |

| Material Initially Disclosed in the Specification | 2.20 |

| Use of Proper Names, Trademarks or Trade Names | 2.25 |

| Reference Signs | 2.27 |

| Terminology | 2.30 |

| Physical Values and Units | 2.33 |

| Generic Statements | 2.38 |

| Reference Documents | 2.4 |

| Chapter III | |

| OF THE SET OF CLAIMS – OF THE CLAIMS | 3.01 |

| General | 3.01 |

| Number | 3.03 |

| Form, Content and Types of Claims | |

| Preamble, Characterising Statement and Characterising Part | 3.04 |

| Technical Features | 3.10 |

| Formulas and Tables | 3 |

| Types of Claims | 3.16 |

| Formulation of Claims | 3. |

| Independent Claims | 3.2 |

| Dependent Demands | 3.30 |

| Clarity and Interpretation of Demands

|

|

| General | 3.36 |

| Inconsistencies – Support in the Specification and Figures | 3.40 |

| Generic Statements | 3.41 |

| Essential Features | 3.42 |

| Use of Relative and/or Imprecise Terms | 3.45 |

| Terms “Consisting of” versus “Comprising” | 3.48 |

| Optional Features | 3.50 |

| Proper Names, Trademarks or Trade Names | 3.51 |

| Definition of the Subject Matter of Protection in Terms of the Result to be Achieved | 3.52 |

| Definition of the Subject Matter of Protection in Terms of Parameters | 3.54 |

| Methods and Means for Measuring Parameters Referred to in the Claims | 3.58 |

| Product Claims by Process | 3.60 |

| Definition by Reference to Use or Another Object | 3.62 |

| The term “in” | 3.69 |

| Claims of Use | 3.73 |

| References to the Specification or Drawings | 3.7 |

| Reference Signs | 3.78 |

| Negative Limitations | 3.8 |

From the Support in the Specification – Article 25 of the IPL

| General Observations | 3.85 | |

| Degree of Generalisation in a Claim | 3.86 | |

| Objection to Lack of Grounds | 3.88 | |

| Lack of Reasoning versus Descriptive Insufficiency | 3.91 | |

| Definition in Terms of Function | 3.93 | |

| Matter Contained in the Set of Claims and Not Mentioned in the Specification

Unit of Invention – Article 22 of the IPL |

3.96 | |

| General | 3.98 | |

| Special Technical Features | 3.10 | |

| Lack of Unity of Invention a Priori or a Posteriori | 3.112 | |

| Intermediate and Final Products | 3.119 | |

| Alternatives (“Markush Groupings”) | 3.126 | |

| Individual Features in a Claim | 3.129 | |

| Dependent Claims | 3.131 | |

| Divisional Application Analysis | 3.133 | |

| Unity of Invention and Double Protection | 3.138 | |

| Chapter IV | ||

| DESIGN | 4.01 | |

| Chapter V | ||

| ABSTRACT | 5.01 | |

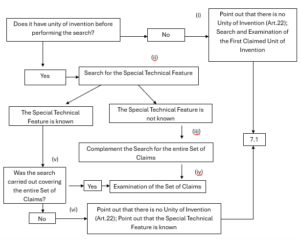

| Appendix I – Flowchart of the Unit of Invention | ||

| Appendix II – History of changes (see pdf version of the English traslation) | ||

CONTENTS OF THE PATENT APPLICATION

Chapter I TITLE

- The title of the application must concisely, clearly and precisely define the technical scope of the invention, and must be the same for the application, the Specification, the abstract, and the sequence listing, if any. The examiner must assess whether the title adequately represents the different categories of claims. It is not mandatory that all independent claims of the same category be represented in the title.

Example: If an application claims more than one alternative for the same category of independent claim, such alternatives may be represented together.

- If the claims undergo category changes, the title must be changed accordingly. In an opinion in which a requirement relating to the title is made, the examiner may suggest a new title.

Chapter II

Specification

Method of Presentation

- The examiner shall verify that the manner of presentation of the specification complies with the following:

- it begins with the title;

- specify the technical field to which the invention relates;

- indicate and describe the state of the art understood as relevant by the applicant for understanding the invention; highlighting existing technical problems;

- disclose the invention as claimed, so that the

technical problem and its solution can be understood, and establish any advantageous effects of the invention in relation to the relevant prior art;

- clearly highlight the novelty and evidence the technical effect achieved;

- relate the figures presented in the drawings, specifying their graphic representations, such as views, sections, circuit diagrams, block diagrams, flowcharts, graphs, etc.;

- describe the invention in a consistent, accurate, clear and sufficient manner, so that a person skilled in the art can carry it out, referring to the reference signs in the drawings, if any, and, where appropriate, using examples and/or comparative tables, and relating them to the state of the art;

- highlight, when appropriate, the best form of execution of the invention known to the applicant on the filing date or priority, if any. The best form of execution applies to all elements considered essential to the invention, even if not claimed.

Example: An invention relates to an elastomeric seal and a method for treating it to manufacture said seal. This method, although not claimed, if considered essential to achieve the distinctive features presented by the seal, must be described in the report since, without the description of the method, the claimed seal cannot be implemented.

- Indicate, explicitly, if this is not inherent in the description or nature of the invention, the manner in which the invention can be used or produced in any type of industry.

- The examiner may allow a presentation different from that specified above only when it enables a better understanding of the invention.

State of the art

- The specification must include the state of the art relevant to the invention, which may be valuable for understanding the invention, searching for and examining the invention.

- Documents cited as representative of the state of the art must be identified, whether patent or non-patent literature, such as scientific articles, newspaper articles and conference proceedings.

- As a result of the examination, the examiner may require the applicant to include references to prior art documents in the Specification of the application, such as documents found during the search, provided that the content of these documents does not extend beyond the disclosure of the invention originally filed in the application.

Technical Problem to be Solved by the Invention and Proof of the Technical Effect Achieved

- The invention must be described in such a way that the technical problem can be understood, as well as the proposed solution. To meet this condition, the details considered necessary to elucidate the invention must be included.

- In accordance with the current Ordinance, the invention must solve technical problems, constituting the solution to such problems, and have a technical effect. Thus, it is necessary to demonstrate the technicalnature of the problem to be solved by the proposed solution. The effects achieved in order to have an invention can be proven later, provided that they do not constitute the addition of new matter.

- A patent application does not necessarily have to describe the optimal solution to the problem to which it refers, and does not necessarily imply that

the technical solution is an advance over the state of the art. Thus, the proposed solution may simply be the search for an alternative that can achieve the same results through different technical means, provided that the patentability requirements are met.

- Documents belonging to the state of the art, identified after filing, i.e., during the search or presented in subsidies to the examination, may cause the application to have its technical problem reformulated and/or replaced by another technical problem. In this case, provided that this reformulation is deductible by a person skilled in the art and inherent to the subject matter initially disclosed, based on the application as filed, such documents may be included in the Specification in order to highlight the contribution of the invention to the prior art.

- The term “inherent” requires that the matter not described be necessarily implicit in the application as filed and that it would be recognised by a person skilled in the art. Inherence cannot be established by probabilities or possibilities. The mere fact that something may result from a given set of circumstances is not sufficient.

- The reformulation of the technical problem, in accordance with the previous paragraph, may not be incorporated into the set of claims. However, it may result in the introduction into the claims of features originally present only in the specification, drawings or abstract at the time of filing, provided that this does not imply a broadening of the scope of the claimed subject matter.

Industrial Applicability

- The specification shall explicitly indicate the manner in which the invention can be exploited in industry, if this is not inherent in the specification or in the nature of the invention.

Descriptive Sufficiency

- Sufficiency of description must be assessed on the basis of the specification, which must present the invention in a sufficiently clear and precise manner so that it can be reproduced by a person skilled in the art. The specification must contain sufficient conditions to ensure that the claimed invention can be realised.

- The definition of a person skilled in the art is broad. A person skilled in the art may be someone with average knowledge of the technique in question at the time of filing the application, with a technical-scientific level, and/or someone with practical operational knowledge of the subject matter. It is considered that such a person had at their disposal the means and ability for routine work and experimentation, usual in the technical field in question. There may be cases where it is more appropriate to think in terms of a group of people, such as a production or research team. This may apply particularly to certain advanced technologies such as computers and nanotechnology.

- In this context, it must be ensured that the application contains sufficient technical information to enable a person skilled in the art to:

- put the invention into practice as claimed without undue experimentation; and

- understand the contribution of the invention to the state of the art to which it belongs.

Undue experimentation means that a person skilled in the art, based on the disclosure of the invention, needs additional experimentation to carry out the invention.

- The description of the theoretical principles that justify the functioning and results achieved by the invention must be presented in the specification in order to better understand the invention. However, this description is not a determining factor in the sufficiency of the description, as this criterion requires only a description that allows the implementation of the invention by a person skilled in the art. In cases where such a description is considered essential for the search and analysis of the application, and for a better understanding of the invention, it must always be included.

Deposit of Biological Material

- When the application concerns biological material that is essential to the practical realisation of the object of the application, cannot be described in the form of Article 24 of the IPL, and is not accessible to the public, the report must be supplemented by the filing date of the patent application by depositing the material with an institution authorised by the INPI or indicated in an international agreement.

- In the absence of an institution located in the country, authorised by the INPI or indicated in an international agreement in force in the country, the applicant may deposit the biological material with any of the international depositary authorities recognised by the Budapest Treaty, which must be done by the filing date of the patent application, and such data must be included in the specification of the patent application.

Sequence Listing

- The applicant for a patent that contains in its subject matter one or more nucleotide and/or amino acid sequences that are fundamental to the description of the invention must represent them in a Sequence Listing to enable the assessment of the descriptive sufficiency referred to in Article 24 of the IPL.

Matter Initially Disclosed in the Specification

- Article 32 of the IPL establishes that, in order to better clarify or define the patent application, the applicant may make changes until the examination request, provided that these are limited to the subject matter initially disclosed in the application. Subject matter disclosed is understood to mean all the subject matter contained in the patent application as a whole: specification, claims, abstract and drawings

(if any).

- There are no objections to the applicant introducing amendments to the specification, relating only to a better description of the state of the art, as well as the elimination of inconsistencies in the text, at any time.

- The inclusion of data, parameters or features of the invention that were not included in the original application constitutes an addition of subject matter and, as such, cannot be accepted.

Example ¹: In a patent application referring to a chemical composition containing several ingredients, an additional ingredient to this composition would be considered an undue addition of matter. Similarly, a patent application describing a bicycle frame without specifying the type of material would imply an addition of matter if the applicant requested an amendment describing the material as aluminium, which is essential to the invention. If this amendment merely represents the state of the art, it would be accepted.

Example ²: In an invention relating to rubber, without at any time explicitly revealing, for example, that the rubber is elastic, an amendment to the specification mentioning this feature may be accepted without constituting an addition of matter, since such a feature is inherent in any rubber, for a person skilled in the art, at the time of filing.

- Amendments to the specification resulting from technical requirements or an unfavorable opinion formulated by the INPI shall be examined. If, on this occasion, the applicant submits voluntary amendments to the specification that are not directly resulting from the examination, these shall also be examined and shall be accepted provided that they are limited to the subject matter initially disclosed in the application.

- After the request for examination, voluntary amendments to the specification may be accepted, provided they are limited to the subject matter initially disclosed in the application.

Use of Proper Names, Registered Trademarks or Trade Names

- The use of proper names, trademarks, trade names or similar words when such words simply refer to the origin or to a set of different products is not permitted.

- Exceptions occur when such words are accepted as standard descriptive terms. In this case, such words are permitted without the need for additional identification with regard to the product to which they relate.

Reference Signs

- Reference signs used in designs must be included in the specification.

- The specification and drawings must be consistent with each other, and reference signs must be defined in the specification.

- Reference signs must be uniform throughout the

Terminology

- The specification should be clear and use recognised technical terms. Technical terms that are rarely used or specially formulated may be accepted, provided they are adequately defined and there is no recognised equivalent in the art.

- This criterion should be extended to foreign terms when there are no equivalents in the vernacular. Terms that already have an established meaning should not be used to mean something different, in order to avoid confusion.

- Terminology should be consistent throughout the

Physical Values and Units

- When properties are used to characterise a material, the relevant units should be specified if quantitative considerations are involved. If this is done by means of a published standard (e.g. a standard for sieve sizes), and a set of initials or similar abbreviation is used to refer to that standard, this information should be included in the specification.

- Units of weight and measurement should be expressed using the International System of Units, its multiples and submultiples, except for terms established in specific technical fields, such as Btu, mesh, barrel, inches. When the unit used differs from the established practice in the sector and the International System of Units, the applicant should provide the corresponding conversion to the International System of Units.

- With regard to geometric, mechanical, electrical, magnetic, thermal, optical and radioactivity indications, the provisions of the current General Table of Units of Measurement established by the competent national body must be observed.

- Chemical formulas and/or mathematical expressions, as well as symbols, atomic weights, nomenclature and specific units not provided for in the General Table of Units of Measurement established by the competent national body, must comply with established practice in the sector.

- The terminology and symbols, as well as the system of units

adopted, must be uniform throughout the application.

Generic statements

- Generic statements in the specification that use vague and imprecise terms, which imply an extension of the subject matter of protection, shall not be admitted, based on Article 24 of the IPL.

- In particular, an objection shall be raised to any statement referring to the extension of protection so as to cover the “spirit” of the invention. An objection shall also be raised to a “combination of features” or to any statement implying that the invention relates not only to the combination as a whole, but also to individual features or their sub-combinations.

Reference Documents

- Documents cited as references in patent applications may relate to the state of the art or to part of the disclosure of the invention. A reference to a document, whether from patent literature or non-patent literature, that relates to the state of the art may be present in the application as originally filed or introduced at a later date (see 2.03).

- When the reference document relates to the invention, the examiner must first consider whether what is in the reference document is in fact essential to the performance of the invention as understood by Article 24 of the IPL:

- if it is not essential, the usual expression “which is incorporated here by reference” or any expression of the same type may be retained in the Specification; and

- if the matter in the referenced document is essential to satisfy the descriptive sufficiency, the examiner must require the deletion of the above-mentioned expression and that the matter be expressly

incorporated into the Specification, since the specification of the application must be self-sufficient, i.e., capable of being understood in relation to the essential features of the invention without reference to any other document.

- This incorporation of essential subject matter or essential features is, however, subject to the restrictions of Article 32 of the IPL, so that:

- protection was initially claimed for such features in order to comply with Article 25 of the IPL;

- such features contribute to solving the technical problem underlying the invention;

- such features clearly belong to the description of the invention as stated in the application and thus to the content of the application as filed; and

- such features are precisely defined and identifiable within the entire technical information in the reference document.

- If the reference document is essential for the realisation of the invention and was not available to the public on the filing date of the application, it can only be accepted as a reference if it was made available to the public by the publication date of the application. In the event of such unavailability, the examiner shall question the descriptive sufficiency of the application on the basis of Article 24 of the IPL.

- In the exceptional case where the application cites a published document that is not accessible to the examiner, and the document is deemed essential for a correct understanding of the invention, such that it is not possible to conduct a meaningful search without knowledge of the content of this document, the examiner shall issue an office action for the applicant to submit the document. In this case, if the reference document is in a foreign language, it must be accompanied by a translation into Portuguese.

- If a copy of this document is not submitted in time to comply with this requirement, and the applicant does not convince the examiner that the document is not essential for conducting a meaningful search, the examiner shall issue an unfavorable opinion, based on insufficient description, pursuant to Article 24 of the IPL, that the unavailability of this document affects the application.

- If a document is referred to in an application as originally filed, the relevant content of the reference document shall be considered part of the content of the application for the purpose of serving as prior art against subsequent applications.

Chapter III

OF THE CLAIMS

General

- The application must contain one or more claims, which must:

- define the subject matter for which protection is sought;

- be clear and precise; and

- be substantiated by the Specification.

- Based on the above, the number of independent and dependent claims must be sufficient to correctly define the subject matter of the application.

Numbering

- Claims shall be numbered consecutively in Arabic numerals.

Form, Content and Types of Claims

Preamble, Characterising Phrase and Characterising Part

- Since, in general, an invention consists of known features and new features, in order to facilitate understanding of what the invention represents, an independent claim must be formulated by:

- an initial part, which preferably corresponds to the title or part of the title corresponding to its respective category;

- where necessary, a preamble containing the features already included in the state of the art; and

- mandatorily the expression “characterised by”, followed by a characterising part containing the particular features of the invention.

- This separation between known elements and new elements is intended only to facilitate this distinction, since it does not alter the scope or coverage of the claim, which will always be determined on the basis of the sum of the features contained in the preamble and in the characterising part.

- It should be noted that the novelty of the features contained after the expression “characterised by” must always be established in relation to the set of features considered known and defined in the preamble.

- If the preamble defines features A and B associated with each other, and the characterising part defines features C and D, it does not matter whether C and/or D are known in themselves, but whether they are known in association with A and B, i.e. not only with A, nor only with B, but with both. For example, a machine that has four distinct elements A, B, C and D, all of which are known from the prior art. However, the machine constitutes an association of these four elements, which may present novelty and inventive activity.

- The formulation of a preamble may not be appropriate in a number of situations where the invention concerns:

- a specific combination of components that are known in themselves;

- amendments of known processes by omitting or replacing a step, as opposed to adding a step;

- amendments of known products by omitting or replacing a constituent, as opposed to adding a constituent; and

- a complex system of functionally interrelated parts, the essence of the invention lying in this

- In the specific case of process patents, it is the set of sequential steps that correctly defines the claim. Thus, even if part of the steps in this process are part of the prior art, it may not be feasible to transpose them in isolation into the preamble of the claim without causing disorder and illogicality in the claimed process. In this case, the correct positioning of the expression “characterised by” must be observed.

Technical Features

- The claims must be drafted in according to the “technical features of the invention”, which means that the claims must not contain features associated with commercial advantages or other non-technical aspects.

Example: A claim describing a tennis shoe equipped with a sole and means for attaching the sole must present in the specification the means that could be used for this purpose, such as buttons, Velcro, etc.

- In a ‘means plus function’ claim, the application of the patent must contain in its specification at least one embodiment in which it presents the structural elements used to achieve such

- According to the current Ordinance, claims with explanatory passages regarding the advantages and simple use of the object are not accepted. In this sense, a distinction must be made between merely explanatory passages and relevant functional features.

- It is not necessary for each of the features of the invention to be expressed solely in terms of its structural elements, but functional features may also be included, provided that a person skilled in the art would have no difficulty in arranging the elements to perform the function at the time of the invention.

- Claims relating to the use of the invention, in the sense of its technical application as contained in the Specification, are permitted.

Formulas and Tables

- Claims, like the Specification, may contain chemical formulas or mathematical expressions, but not drawings. Claims may contain tables only when essential to the clarity of the subject matter claimed.

Types of Claims

- There are only two types of claims: “product claims”, which refer to a physical entity, and “process claims”, which refer to any activity in which a material product is necessary to carry out the process. The activity may be performed on material products, on energy and/or on other processes, such as in control processes.

- Examples of categories of “product claims” include: product, apparatus, object, article, equipment, machine, device, system of cooperating equipment, compound, composition and kit; and examples of “process claims” include: process, use and method.

- For all intents and purposes, process and method are

- The same application may contain claims from one or more categories, provided that they are linked by the same inventive concept.

Formulation of Claims

- The formulation of claims must:

- be preceded by its category and contain the expression “characterised by”;

- define, clearly and precisely and in a positive manner, the technical features to be protected by it;

- be fully substantiated in the Specification;

- not contain, with regard to the features of the invention, references to the specification or drawings, such as “as described in the specification” or “as represented by the drawings”;

- be accompanied, when the application contains drawings, by their technical features, in parentheses, by the respective reference signs contained in the drawings if deemed necessary for its understanding, it being understood that such reference signs are not limiting the claims;

- be written without interruption by full stops;

- not contain explanatory passages regarding the advantages and simple use of the object, as these will not be accepted.

Independent Claims

- Independent claims are those that seek to protect essential and specific technical features of the invention in its

- For each category of claim, there may be at least one independent claim.

- The examiner should bear in mind that the presence of claims of different categories drafted differently but apparently having a similar effect is an option for protection available to the applicant, which the examiner should not oppose by taking a strict approach, but rather by avoiding an unnecessary proliferation of independent claims.

- Each independent claim must correspond to a specific set of features essential to the realisation of the invention, and more than one independent claim of the same category will only be allowed if such claims define different sets of alternative features essential to the realisation of the invention, linked by the same inventive concept.

- Interrelated independent claims of different categories linked by the same inventive concept, where one of the categories is specially adapted to the other, should be formulated in such a way as to highlight their interconnection, i.e. by using expressions such as “Apparatus for carrying out the process defined in claim…” at the beginning of the claim. “Process for obtaining the product defined in the claim…”.

- Examples of interrelated claims are:

- plug and socket, for interconnection;

- respective transmitter and receiver;

- final chemical product and intermediate(s);

- gene, gene construction, host, protein and medicine; and

- product and use of the

- Independent claims shall contain, before the expression “characterised by”, a preamble, where necessary, explaining the essential features for the definition of the subject matter claimed and already included in the state of the art (see 3.04).

- After the expression “characterised by”, the essential and particular technical features which, in combination with the aspects explained in the preamble, are to be protected must be defined (see 3.04).

- Independent claims may serve as the basis for one or more dependent claims and should be grouped by category.

Dependent Claims

- Dependent claims are those that include all the features of one or more preceding claims and define details of those features and/or additional features that are not considered essential features of the invention, and must contain an indication of dependence on those claims and the expression “characterised by”.

- Dependent claims must not exceed the limitations of the features included in the claim(s) to which they refer.

- Dependent claims must define their dependency relationships precisely and comprehensively, and formulations such as “according to one or more of the claims…”, “in accordance with the preceding claims…”, “in accordance with any of the preceding claims”, “in accordance with one of the preceding claims” or similar are not permitted. The draft “in accordance with any of the preceding claims” is acceptable.

- Any dependent claim that refers to more than one claim, i.e., a multiple dependency claim, shall refer to those claims in either an alternative or additive form, provided that the dependency relationships of the claims are structured in such a way as to allow immediate understanding of the possible combinations resulting from those dependencies.

- Multiple dependency claims, whether in alternative or additive form, may serve as the basis for any other multiple dependency claim, provided that the dependency relationships of the claims are structured in such a way as to allow immediate understanding of the possible combinations resulting from these dependencies.

- All dependent claims that refer to one or more previous claims shall be grouped together in order to bring conciseness to the structure of the set of claims.

Clarity and Interpretation of Claims

General

- The requirement that claims must be clear applies to individual claims as well as to the set of claims as a whole. The clarity of claims is of fundamental importance, since they define the subject matter of the protection. Thus, the meaning of the terms of the claims must be clear to a person skilled in the art from the wording of the claim, based on the specification and drawings, if any. In view of the differences in the scope of protection achieved by different categories of claims, the examiner must ensure that the wording of the claim is clear for the category it

- Claims are interpreted based on the specification and drawings (and sequence listing, if any), as well as on the general knowledge of the person skilled in the art at the filing date. When the specification defines any particular term appearing in the claim, then that definition is used to interpret the claim.

- In the case of Markush claims, the examiner shall ensure that the processes described in the report substantially enable the preparation of all claimed compounds, i.e., the examples shall be representative of all classes of claimed compounds, or all such classes shall be sufficiently described in the specification.

- In cases where the skilled person cannot carry out the invention as claimed, or where this would involve an undue amount of experimentation, the generic claims should be restricted to the embodiments mentioned in the Specification.

Inconsistencies ― Basis in the Specification and Figures

- Any inconsistency between the specification and the set of claims should not be accepted, as it raises doubts about the extent of protection and makes the set of claims unclear or unsupported by the specification. Such inconsistencies may be of the following types:

- Simple verbal inconsistency – When the specification necessarily limits itself to a specific feature, but the claims do not follow this limitation, the inconsistency can be remedied by adapting the set of claims to the specification, in order to restrict its scope, based on Article 25 of the IPL and with special attention to Article 32 of the IPL. If the specification refers to a specific feature, for example, screws, and the set of claims seekk fastening means in general, and the examiner understands that the invention is not necessarily limited to screws, it is understood that there is no inconsistency between the specification and the set of claims. Another situation occurs when the claim presents a limitation, but the report does not place particular emphasis on this feature. In such a case, there is no inconsistency between the specification and the set of claims.

- Inconsistency relating to apparently essential features – If it is common knowledge in the art or established or implied in the invention that a particular technical feature present in the Specification is considered essential for the realisation of the invention, but is not mentioned in an independent claim, such a claim should not be allowed by the examiner, based on Article 25 of the IPL.

Generic Statements

- As in the Specification, generic statements in the set of claims that imply that the scope of protection can be extended in a vague and imprecisely defined manner constitute an irregularity under Article 25 of the IPL. In particular, objection should be raised to any statement referring to the scope of protection being broadened to cover the “spirit” of the invention. Objections should also be raised to claims directed to a combination of features, to any statement that appears to imply that protection is sought not only for the combination as a whole, but also for individual features or their sub-combinations.

Essential Features

- An independent claim must explicitly specify all essential features necessary to define the invention, except if such features are implied by the generic terms used. That is, a “bicycle” need not mention the presence of wheels.

- If a claim refers to a product that is of a well-known type and the invention lies in the modification of certain aspects, it is sufficient for the claim to clearly identify the product, specify what is modified and how it is modified. Similar considerations apply to claims for an apparatus.

- The patentability of the invention depends on the technical effect achieved, so the claims must be formulated to include all the technical features that are considered essential for achieving the technical effect, as contained in the specification.

Use of Relative and/or Imprecise Terms

- The use of relative terms such as “large,” “wide,” “strong,” among others, in a claim is not permitted, except where they have a well-established meaning in the particular art, for example, “high-frequency” in relation to an amplifier, and this is the intended meaning. A relative term that does not have such a meaning should be replaced by a more precise term or by another term already described in the report as filed.

- Imprecise words or expressions, such as “about,” “substantially,” “approximately,” among others, are not allowed in a claim, regardless of whether they are considered essential to the invention.

- In the case of the use of relative terms or imprecise expressions in the claim, the examiner shall allege lack of clarity. Counterarguments by the applicant to the effect that elements missing from the text belong to the prior art cannot be accepted, since the problems of lack of clarity will persist. Furthermore, the inclusion of these elements in the text is considered an addition of new matter and is therefore not permitted.

Terms “Consisting of” versus ” Comprising “

- The terms “consisting of” and “comprising”, as well as their derivatives, are considered closed terms defining the invention. That is, if a claim deals with a “chemical composition characterised by consisting of components A, B and C”, the presence of any additional components is excluded.

- The terms “compreender” (comprising), “conter” (containing), “englobar” (encompassing) and “incluir” (including), as well as their derivatives, are considered open terms defining the invention, i.e., in the above example, the form “characterised by comprising components A, B and C” is not limited to only these elements and may be accepted, provided that such elements are essential for the realisation of the invention.

Optional Features

- Expressions such as “preferably,” “for example,” “such as,” “more particularly,” or similar expressions should be examined with particular care to ensure that they do not introduce ambiguity. Such expressions have no limiting effect on the scope of a claim, i.e., the feature following any such expression should be considered entirely optional.

Example: In a process claim that claims the temperature parameter “…in the range of 80ºC to 120ºC, preferably 100ºC”, the term “preferably” does not introduce ambiguity.

Proper Names, Registered Trademarks or Trade Names

- Proper names, trademarks or trade names in claims should not be allowed, since there is no guarantee that the product or feature associated with a trademark or similar cannot be modified during the term of the patent. They may be authorised, exceptionally, if their use is unavoidable and if they are generally recognised as having a precise meaning.

Definition of the Subject Matter of Protection in Terms of the Result to be Achieved

- As a general rule, claims that define the invention by the result to be achieved should not be allowed, in particular if they merely claim the technical problem involved. However, they may be allowed if the invention can only be defined in such terms or cannot be defined more precisely without unduly restricting the scope of the claims, and if the result is such that it can be directly and positively verified by tests or procedures adequately specified in the Specification, or known to a person skilled in the art, and which do not require undue experimentation.

Example: A claim dealing with a material characterised by being capable of extinguishing cigarette flames and whose specification presents the chemical composition of this material would not be accepted, since the material can be characterised by its chemical composition, and not by the result to be achieved by the invention.

- It should be noted that the above requirement for defining the subject matter of protection in terms of the result to be achieved differs from those for defining the subject matter of protection in terms of functional features (see 3.97).

Definition of Protection Material in Terms of Parameters

- Parameters are features, which can be directly measurable properties, such as the melting point of a substance, the bending strength of steel, the electrical resistance of a conductor, or can be defined as mathematical combinations containing several variables in the form of formulas.

- The characterisation of a product by means of its parameters should only be permitted in cases where the invention cannot be adequately defined in any other way, provided that these parameters can be clearly and reliably determined, either by the indications in the specification or by objective procedures that are common in the state of the art. The same applies to a process-related feature that is defined by means of parameters.

- Cases in which unusual parameters are used, even if sufficiently described, are not admissible at first glance due to lack of clarity, since no meaningful comparison with the prior art can be made. Such cases may also mask a lack of novelty. In such cases, it is up to the applicant to prove, in the specification, the equivalence between the unusual parameter(s) used and those used in the prior art, which does not constitute an addition of matter.

- The case in which the method and means for measuring the parameters also need to be presented in the claim is dealt with in item 3.58.

Methods and Means for Measuring Parameters Referred to in Claims

- The invention should be defined completely in the claim itself. In principle, the measurement method is necessary for the unambiguous definition of the parameter. However, the method and means of measuring the parameter values are not necessary in the claims when:

- the description of the method is so long that its inclusion would render the claim unclear due to lack of conciseness or difficulty of understanding;

- a person skilled in the art would know which method to use, for example because there is only one method, or because a particular method is routinely used; or

- all known methods achieve the same result — within the limits of measurement accuracy.

- However, in all other cases, the method and means of measurement must be included in the claims, since they define the subject matter for which protection is sought.

Product Claims by Process

- Claims for a product defined in terms of a manufacturing process are only allowed if the products meet the requirements for patentability, i.e. that they are new and inventive, provided that the product cannot be described in any other way. A product is not considered new simply because it is produced by a new process. As regards the novelty analysis, a product claim X obtained by process Y is devoid of novelty when a prior art for the same product X is found, regardless of the method of obtaining it.

- A claim defining a product in terms of a process should be interpreted as a product claim as such. The claim may, for example, take the form “Product X characterised in that it is obtained by process Y”. Regardless of whether the term “obtain”, “obtained”, “directly obtained” or an equivalent expression is used in the product-by-process claim, the claim is still directed to the product itself and confers absolute protection for the This type of claim should only be accepted when it is not possible to adequately define the product per se, but rather only by the manufacturing process itself.

Example: A material is prepared including a new sintering step. The resulting product has distinctive features of greater mechanical strength compared to the state of the art of materials with the same nominal composition, but the applicant is unable to describe the material per se. In this case, the product can be described in terms of the product obtained by the process.

Definition by Reference to Use or to Another Object

- When a product claim (see 3.16) defines the invention by reference to features related to its use, this may result in lack of clarity.

- Consider the case where the claim not only defines the product itself, but also specifies its relationship to a second product that is not part of the claimed product.

Example: An engine head, where the first is defined by features of its location on the latter.

- Before considering a restriction on the combination of the two products, it should be remembered that the applicant is entitled to independent protection for the first product.

Example: A claim for a “cylinder head connected to an engine” cannot be modified to “cylinder head connectable to an engine” or to the cylinder head itself, as this is considered a violation of Article 32 of the IPL, even if this change is supported by the specification initially disclosed.

- On the other hand, since the first product can often be produced and marketed independently of the second product, a claim for a ‘cylinder head connectable to a motor’, initially claimed, may be amended to ‘Cylinder head connected to a motor’ or to the head itself. If it is not possible to provide a clear definition of the first product on its own, then the claim should be directed to a combination of the first and second products ― “Cylinder head connected to a motor” or “Motor with cylinder head”.

- It may also be permissible to define the dimensions and/or shape of a first object in an independent claim by general reference to the corresponding dimensions and/or shape of a second object that is not part of the first claimed entity but is related to it by use. This applies especially when the size of the second object is in some way

Example: In the case of a mounting bracket for a vehicle number plate, where the frame of the bracket and fastening elements are defined in relation to the external shape of the plate.

- However, references to second entities that cannot be seen as objects of standardisation may also be sufficiently clear in cases where a person skilled in the art would have little difficulty in inferring the restriction resulting from the scope of protection of the first object.

Example: In the case of a cover for a round agricultural bay, where the length and width of the cover are defined in relation to the dimensions of the bay.

- It is not necessary for such claims to contain the exact dimensions of the second entity, nor to refer to a combination of first and second entities. Specifying the length, width and/or height of the first entity without reference to the second would lead to an undue restriction of the scope of protection.

The term “in”

- To avoid ambiguity, the word “in” should be examined with special attention in claims where it defines a relationship between different physical entities (product, equipment), or between entities and activities (process, use), or between different activities. Examples of claims that use the word “in” in this context are:

- Cylinder head in a four-stroke engine, characterised by…;

- Tone dialling detector in a telephone apparatus with an automatic dialler, the tone dialling detector characterised by…;

- Method for controlling the current and voltage in a process using means for supplying an electrode of arc welding equipment, characterised by the following steps:…; or

- Improvement X… in a process/system/equipment etc. characterised by…

- In the claims of the type indicated by examples (i) to (iii), the emphasis is on the full functionality of the sub-units, i.e. “engine cylinder head, tone dialling detector, method for controlling the current and voltage of arc welding”, rather than the complete unit within which the sub-unit is contained, four-stroke engine, telephone, the welding process. This may constitute a lack of clarity if the protection application is limited to the sub-unit alone, or if the unit as a whole is to be protected.

- For the sake of clarity, claims of this type should be directed either to “a unit with — or comprising — a sub-unit”, i.e. “four-stroke engine with a cylinder head”, or to the sub-unit alone, specifying its purpose, “cylinder head for a four-stroke engine”.

- In claims of the type indicated by example (iv), the use of the word “in” does not make it clear whether protection is sought only for the improvement or for all the features defined in the claim. Here, too, it is essential to ensure that the text is clear. However, claims such as “Use of a substance X characterised by being in an ink or varnish composition” are acceptable on the basis of a second use.

Use claims

- For examination purposes, a “use” claim in the form of “use of substance X as an insecticide” should be considered equivalent to a “process” claim in the form of “a process for killing insects using substance X” or “use of alloy X for manufacturing a particular part”. Thus, a claim in the form indicated should not be interpreted as directed to substance X, which is known, but as intended for the use as defined, i.e., as an insecticide or for manufacturing a particular article. However, a claim directed to the use of a process is equivalent to a claim directed to the same

- Independent claims of the type “Product characterised by use”, in which the product is already known in the prior art, are not accepted due to lack of novelty. In cases where a product is not known in the prior art, such a claim formulation is not accepted due to lack of clarity, in accordance with Article 25 of the IPL, since the product must be defined in terms of its technical features (see 3.10).

- In the pharmaceutical field, claims involving the use of chemical-pharmaceutical products for the treatment of a new disease use a format conventionally called a Swiss formula:

“Use of a compound of formula X, characterised in that it is for preparing a medicament for treating disease Y.”

- It should be noted that this type of claim confers protection for the use, but does not confer protection for the therapeutic method, which is not considered an invention according to item VIII of Art. 10 of the IPL. Claims of the type “Use for treatment”, “Process/Method for treatment”, “Administration for treatment” or their equivalents correspond to therapeutic method claims and, therefore, are not considered inventions according to item VIII of Article 10 of the IPL.

References to the Specification or Drawings

- Claims should not, in relation to the technical features of the invention, make references to the specification or drawings, such as “as described in the part of the specification” or “as illustrated in

Figure 2 of the drawings”.

Reference Signs

- When the application contains drawings, the technical features defined in the claims must be accompanied, in parentheses, by the respective reference signs contained in the drawings if deemed necessary for understanding the same, it being understood that such reference signs are not limiting the claims. If there are a large number of alternatives for the same feature, only the reference signs necessary for understanding the claim shall be included.

- The reference signs, numbers and/or letters must be inserted not only in the characterising part, but also in the preamble of the claims, provided that they accurately identify the elements referred to in the drawings.

- Text associated with reference signs in the claims is not allowed in parentheses. Expressions such as “fastening means (screws 13, nail 14)” or “valve assembly (valve seat 23, valve element 27, valve seat 28)” are special features to which the concept of reference signs does not apply. Consequently, it is unclear whether the features added to the reference signs are limiting or not. In this sense, the correct wording should be, for example: “the hose (4) is connected to the valve (10)”, rather than “the hose is connected to the valve”, or “4 is connected to 10”.

- Lack of clarity also arises with expressions in parentheses that do not include reference signs, i.e., “Moulded (concrete) brick”. In contrast, expressions in parentheses with a generally accepted meaning are acceptable, as in the case of “(meta)acrylate”, which is a known form that covers both acrylate and methacrylate. The use of parentheses in chemistry or mathematical expressions is also acceptable.

- However, the opposite may be allowed, i.e., drawings may contain more reference signs than those contained in the set of claims.

Negative Limitations

- Each claim must clearly and precisely define, in a positive manner, the technical features to be protected by it, avoiding expressions that lead to indefiniteness in the claim.

- However, negative limitations may be used only if the addition of positive features in the claim does not clearly and concisely define the subject matter to be protected, or if such addition unduly limits the scope of the application.

Example ¹: Process for producing expandable polystyrene in bead form (EPS) by polymerising styrene in aqueous suspension in the presence of suspension stabilisers and conventional styrene-soluble polymerisation initiators… characterised in that the polymerisation is carried out in the absence of a chain transfer agent.

Example ²: Compound of formula 1, characterised in that R1 is halogen, with the exception of R1 being chlorine.

From the grounds in the Specification – Article 25 of the IPL

General

- Article 25 of the IPL establishes that claims must be based on the Specification, characterising the particularities of the application and defining, in a clear and precise manner, the subject matter of the protection. This means that there must be a basis in the specification for the subject matter of each claim and that the scope of the claims must not be broader than the content of the specification and drawings, if any, and based on the contribution to the state of the art.

Degree of Generalisation in a Claim

- The proper formulation of a claim must meet the condition of precision set forth in Article 25 of the IPL. Most claims are generalisations of one or more particular examples. The degree of generalisation allowed is a matter that the examiner must analyse in each case in light of the relevant state of the art.

- An invention that opens up a whole new field is entitled to more generalities in the claim than one that refers to advances in an already known technology.

Objection to lack of support

- A generic claim, i.e., one relating to an entire class, such as materials or machines, may be allowed, even if broad in scope, if there is support in the Specification. Whenever the information provided appears insufficient to enable a person skilled in the art to carry out the claimed subject matter using routine methods of experimentation or analysis, the examiner shall raise an objection so that the applicant may present arguments to the effect that the invention can in fact

be readily applied on the basis of the information given in the Specification or, in the absence thereof, restrict the claim accordingly.

- Once the examiner has established that a broad claim is not supported by the specification, the burden of proving otherwise lies with the applicant. In this case, the examiner may rely on a published document to support their reasons.

- The question of the support is illustrated by the following examples:

Example ¹: A claim refers to a process for treating all species of plant seedlings by subjecting them to a controlled cold shock in order to produce specific results, whereas in the specification, the process applies only to one species of plant. Since it is well known that plants vary widely in their features, there are well-founded reasons to believe that the process is not applicable to all plant seedlings. Unless the applicant can provide convincing evidence that the process is nevertheless of general application, it should restrict the set of claims to the plant species referred to in the specification. A mere assertion that the process is applicable to all plant seedlings is not sufficient;

Example ²: A claim refers to a specific method of treating “synthetic resin moulds” to obtain certain changes in the physical features of the resin. All the examples described relate to thermoplastic resins and the method is such that it appears to be unsuitable for thermosetting resins. Unless the applicant can demonstrate that the method is nevertheless applicable to thermosetting resins, it should restrict its claim to thermoplastic resins; and

Example ³: A claim refers to fuel oil compositions that have a certain desired property. The Specification provides support for obtaining fuel oils with this property, achieved through the presence of defined quantities of a certain additive. No other way of obtaining fuel oils with the desired property is described in the Specification. The claim makes no mention of the additive. In this case, the claim is not fully supported by the specification.

Lack of support versus insufficient description

- It should be noted that, although an objection of lack of grounds is an objection under Article 25 of the IPL, it can often, as in the examples in item 3.94, also be considered as an objection of insufficient description of the invention under Article 24 of the IPL (see item 2.13). In this context, the objection lies in the fact that the application, as disclosed, is insufficient to enable a person skilled in the art to carry out the “invention” throughout the entire field claimed, although it is sufficient in relation to a more restricted “invention”. Both conditions are required in order to uphold the principle that the wording of a claim must be based on the specification of the application.

- It should be noted that the descriptive sufficiency of the invention must be verified only in the specification, while Article 25 refers to the grounds for the set of claims in the specification.

Definition in Terms of Function

- A claim may broadly define a feature in terms of its function, i.e. as a functional feature, even when only one example of the feature has been given in the specification, if the person skilled in the art considers that other means can be used for the same function (see also 3.10 and 3.53).

- The expression “terminal position detection means” in a claim may be supported by a single example comprising a limit switch, it being obvious to the skilled person that a photoelectric cell or an extensometer could also be used.

- However, if the entire content of the application gives the impression that a function must be performed in a particular manner, without any indication that alternative means are envisaged, and a claim is formulated in such a way as to cover other means, or all means, of performing the function, then such a claim is not admissible. In this case, the Specification does not support the set of claims when it merely states, in vague terms, that other means may be used, if there is no clarity as to what they may be or how they may be used, thereby violating Article 25. The claim must therefore be reformulated in order to restrict it.

Matter Contained in the Set of Claims and Not Mentioned in the Specification

- When certain subject matter that is the object of protection is clearly disclosed in a claim of the application as filed, but is not mentioned anywhere in the specification, it is permissible to include such subject matter in the specification, provided that its content complies with Article 24 of the IPL.

- The reverse situation, i.e., subject matter contained in the specification and not claimed until the request for examination of the application, may not be claimed, except in the case of a restriction of the set of claims.

Unity of Invention – Article 22 of the IPL General Considerations

- The patent application of the application must refer to a single invention or a group of inventions that are interrelated in such a way as to comprise a single inventive concept. When a patent application refers to a group of inventions that are interrelated in such a way as to comprise a single inventive concept, it may give rise to a plurality of independent claims in the same category, provided that they define different sets of alternative features that are essential to the realisation of the invention (see 3.21).

- By single inventive concept, or unity of invention, it is understood that the various inventions claimed have a technical relationship with each other represented by one or more special technical features that are the same or corresponding for all the claimed inventions.

- The expression “special technical features” refers to technical features that represent a contribution that the claimed invention brings in relation to the state of the art, interpreted on the basis of the Specification and drawings, if any, and which are common or related to each of the claimed inventions. Once the special technical features for each of the inventions have been identified, it must be determined whether or not there is a technical relationship between the inventions conferred by the aforementioned special technical features.

- It should be noted that, in a first analysis, the unity of invention must be considered among the independent claims of the application.

- In the absence of novelty or inventive step in an independent claim, the other dependent claims should be analysed not only in terms of their merits, but also in terms of the existence of a common inventive concept (see also 3.135).

- Whenever the application does not present unity of invention, the examiner must raise an objection based on Article 22 of the IPL.

Special Technical Features

- The interrelationship between inventions required by Article 22 of the IPL must be a technical relationship, which is expressed in the claims in terms of the same or corresponding special technical features. The expression “special technical features” means, in any claim, one or more technical features that represent a contribution that the claimed invention makes in relation to the state of the art, interpreted on the basis of the Specification and the drawings, if any, and which are common to or related to each of the claimed inventions. Once the technical specificities of each invention have been identified, it is necessary to determine whether or not there is a technical relationship between the inventions, and whether or not this relationship involves these special technical features. It is not necessary for the special technical features in each invention to be the same. The required interrelationship may be found between the corresponding special technical features.

Example: In a given claim, the special technical feature that provides resilience is a metal spring, whereas in another claim it is a rubber block.

- In the case of interrelated elements, these must be specially adapted to each other. In the case where these elements have several other applications and the aforementioned relationship is only one of several possible ones, it is understood that the interrelationship necessary for unity of invention does not exist.

Example: In a claim dealing with a non-slip artificial lawn, another claim is presented dealing with a football made from material specially suited to this turf, which can also be used on other types of turf. In this case, it is understood that there is no unity of invention, even though the ball performs better on the turf mentioned.

- A plurality of independent claims in different categories may constitute a group of inventions interrelated in such a way as to form a single inventive concept. The following combinations of claims from different categories are permitted in the same application, as shown in the following examples:

Example ¹: an independent claim for a given product, an independent claim for a process specially adapted for the manufacture of that product, and an independent claim for a use of that product; or

Example ²: an independent claim for a given process, and an independent claim for an apparatus or means specifically designed to carry out the said process; or

Example ³: an independent claim for a given product, an independent claim for a process specially adapted for the manufacture of said product, and an independent claim for an apparatus or means specifically designed for carrying out that process.

- In the claim of the type indicated by example (i), the process is specially adapted for the manufacture of the product if the process results in the claimed product, i.e. if the process is in fact suitable for achieving the claimed product and therefore defines a special technical feature between the claimed product and process. A manufacturing process and its product cannot be considered to lack unity of invention simply by virtue of the fact that the manufacturing process is not limited to the manufacture of the claimed product.

- In the claim of the type indicated by example (ii), the apparatus or medium is specifically designed for carrying out the process if the apparatus or medium is suitable for carrying out the process and thus defines a special technical feature between the claimed apparatus or medium and the claimed process. On the other hand, it is irrelevant whether the apparatus or means could also be used to carry out another process or whether the process could also be carried out using an alternative apparatus or means.

- Unity of invention may exist in an application claiming claims in one or more different technical fields, provided that there is a common or corresponding “special technical feature” between these

Example: An application has an independent claim relating to a polymer G, as well as another independent claim relating to artificial grass made from polymer G, used on football pitches. In this case, although the technical fields are different, there is unity of invention in the application, since polymer G is the common “special technical feature” between these claims.

- An application may contain more than one independent claim in the same category only if the subject matter of the protection involves one of the following cases:

- a bunch of products that are connected;

- different uses of a product or equipment; or

- different sets of alternative features that are essential to the realisation of the invention, linked by the same inventive concept.

- Furthermore, it is essential that a single general inventive concept links the claims in different categories. The presence in each claim of expressions such as “specially adapted” or “specifically designed” does not necessarily imply that a single general inventive concept is present.

Lack of unity of invention a priori or a posteriori

- The lack of unity of invention can be evidenced directly a priori, i.e., by considering the claims without conducting a prior art search, or it may only be apparent a posteriori, i.e., after taking into account the state of the art, consisting of the documents possibly submitted in the application, as well as those found during the search.

- In an a posteriori analysis of unity of invention, if one or more documents in the state of the art relevant to the invention show that the special technical feature is known, the independent claims must be analysed for the existence of another special technical feature common to them (see also 3.135 with reference to dependent claims).

- A flowchart for processing the analysis of unity of invention is presented in Appendix I of these Guidelines.

- Once the lack of unity of invention in an application has been considered a priori, it must be reported by the examiner in a technical unfavorable opinion, which shall include considerations to clearly and precisely identify the different units of invention present in the application, or interconnected and unified groups of inventions, informing the applicant of the need to exclude claims that exceed the unity of invention and/or to divide the application, based on Article 22 of the IPL [item (i) of the flowchart]. In this case, the search report and technical opinion shall be issued based on the first unit of invention claimed. The examiner shall await the applicant’s response, after which he may:

- reject the application for lack of unity, due to the applicant’s failure to provide technical grounds to justify the existence of unity of invention in the application without amendments; or

- continue the examination of the application if the applicant presents convincing arguments for the existence of unity of invention, or the set of claims has been restricted to a single inventive concept.

- Considering the existence of unity of invention a priori, through the identification of the special technical feature among the claims, the examiner must search for this feature among the independent claims [item (ii) of the flowchart]. If such a feature is not known in the prior art, the application has a posteriori unity of invention, and the examiner must supplement the search for the entire set of claims [item (iii) of the flowchart], and then proceed to the substantive examination of the application [item of the flowchart]. If such a feature is known from the prior art, the examiner must assess whether the search carried out was sufficient to cover all the subject matter claimed in the set of claims [item (v) of the flowchart]. If so, the examiner must proceed to the substantive examination of the application [item (iv) of the flowchart]. If not, the application does not have unity of invention a posteriori, and the examiner must inform the applicant based on Article 22 of the IPL [item (vi) of the flowchart] and submit a search report, proceeding in the same way as in the case of lack of unity of invention a priori with the performance of a search [item (i) of the flowchart].

- The lack of unity of invention should not be raised or persisted with on the basis of a strict interpretation. This is particularly true in cases where the examiner finds that the additional effort to be expended in searching the application is minimal (see item (iv) of the flowchart in Appendix I).

- An application that has several classifications relating to its independent claims does not necessarily indicate that there is no unity of invention. There should be a practical and comprehensive consideration of the degree of interdependence of the inventions presented, in relation to the state of the art disclosed by the search report.

Intermediate and Final Products

- The condition of unity of invention must be considered present in the context of intermediate and final products, where:

- the intermediate and final products have the same essential structural element, i.e., their basic chemical structures are the same or their chemical structures are technically and closely interrelated, the intermediate product incorporating an essential structural element in the final product; and

- the intermediate and final products are technically interrelated, i.e., the final product is produced directly from the intermediate or is separated from it by a small number of intermediates, all containing the same essential structural element.

- The unity of invention may also be present between intermediate and final products whose structures are not known, for example, between an intermediate with a known structure and a final product with an unknown structure, or between an intermediate with an unknown structure and a final product with an unknown structure. In such cases, in order to meet the criterion of unity of invention, there must be sufficient evidence to conclude that the intermediate and final products are technically and closely interrelated, for example, when the intermediate contains the same essential element as the final product or incorporates an essential element into the final product.

- Different intermediate products used in different processes for the preparation of the final product may be claimed, provided that they have the same essential structural element. The intermediate and final products must not be separated, in the process leading from one to the other, by an intermediate that is not new, which represents the special technical feature that confers unity of invention between the intermediate and final products. When different intermediates for different structural parts of the final product are claimed, unity is not present between the intermediates. If the intermediate and final products are families of compounds, each intermediate compound must correspond to a compound claimed in the family of final products. However, some of the final products may not have a corresponding compound in the family of intermediate products, so that the two families need not be absolutely congruent.

- The mere fact that, in addition to their ability to be used to produce final products, the intermediates also have other possible effects or properties should not prejudice the unity of the invention.

- Intermediate products are illustrated in the following examples:

Example ¹: Claim 1: New compound having a structure A

— intermediate compound

Claim 2: Product prepared by the reaction of the intermediate compound with structure A with a compound X ― final product

Example ²: Claim 1: Product of the reaction of A and B — intermediate;

Claim 2: Product prepared by the reaction of the intermediate compound with substances X and Y — final product.

- In the types indicated by examples 1 and 2, the chemical structures of the intermediate and/or final products are not known. In example 1, the structure of the product of claim 2 — final product — is not known. In example 2, the structures of the products of claim 1 — intermediate — and claim 2 — final product — are unknown.

- There is unity of invention if there is evidence leading to the conclusion that the inventive feature of the final product depends on the features of the intermediate. If the purpose of using the intermediates in the types indicated by examples 1 and 2 is to amend certain properties of the final product. The evidence may be found in the data presented in the Specification showing the effect of the intermediate on the final product. If there is no such evidence, then there is no unity of invention based on the relationship between the intermediate and final products.

Alternatives – “Markush Groupings”

- When Markush grouping deals with alternatives for chemical compounds, they will be considered to be of a similar nature, provided that the following criteria are met:

(i) all alternatives have a property or activity in common; and

- a common structure is present, i.e., a significant structural element is shared by all alternatives, or, in cases where the common structure cannot be the criterion bringing unity of invention, all alternatives belong to a recognised class of chemical compounds of the prior art to which the invention belongs.

- The verification of whether a group of inventions is interconnected so as to form a single general inventive concept must be made independently of whether the inventions are claimed in separate claims or in the form of alternatives contained in a single claim.